Blue at Gimp Parade is spending the US Thanksgiving week writing about disability issues among Native Americans. I'll join her with this post. Years ago, I was studying someone who studied California's native cultures, and came across Ciqneqs, a "simple simon" character from Chumash legends.

Blue at Gimp Parade is spending the US Thanksgiving week writing about disability issues among Native Americans. I'll join her with this post. Years ago, I was studying someone who studied California's native cultures, and came across Ciqneqs, a "simple simon" character from Chumash legends.[Detour: The Chumash language is transcribed into our alphabet using some diacritical marks and some characters we don't ever use (a question mark without the dot, for example). I can't type them in here. Ciq?neq?s is actually written by two of those question marks, and the C and S have marks on top of them. I have no idea how it's pronounced--I've only read it on the silent page, and said "Sick-nex," which is unlikely to be accurate.]

These stories are found in the book December's Child: A Book of Chumash Oral Narratives (UC Press 1975) by Thomas Blackburn. Blackburn compiled Chumash oral narratives collected by the Smithsonian (I don't remember whether Blackburn or someone before him translated these into English, though). The book gives exact sources--which person told which tales to the original folklorists--but I didn't copy those over when I was reading. There are two Ciq?neq?s stories in the book; this is the longer one, but it's more interesting to my eye.

Once there was a village with only a few families living in it, and in two of these families there was a man and woman who married one another when they came of age. After their marriage, they began to have children, and their first twelve children were all boys. The last, however, was a girl. The children all grew up, and one day it was discovered that the girl was pregnant.... [section about a makeshift paternity test omitted here]There are other Ciqneqs stories, but this one has most of the usual elements of it--taking orders literally, giving cryptic answers to all inquiries, going unpunished because he's a "child of the clouds." He frustrates the Yowoyow, the devil, in another story, with his strange conversational style, until the devil gives up and goes away disgusted. He sings a creepy song to scare away his fellow villagers, ending with the line, "I am son of the dead, and therefore I am hungry." He kills a little brother in his care by misconstruing the directions his parents left him. He tries to bed his sister after misunderstanding his grandmother's instructions to marry. "Siqneqs did many other stupid things, but his parents always sent him on errands anyway," explains one storyteller. "And even today, when parents scold their children they're apt to say, 'That's just like Siqneqs!'"

When the child was born the brothers called the ?alaxlaps to come and name him. (The ?alaxlaps was a kind of priest. He could tell whether or not a person would be fortunate in his transactions, and also by the planet of a person what would be his or her fate. He was an anatomist, physiognomist, and astrologer.) The ?alaxlaps asked who the child's father was. One brother said to ask the child's mother. Then the mother said her baby was a sowing of the clouds. When the ?alaxlaps heard this, he said to her: "Ah, girl, you were born to be happy. For it is your lot to give birth to this child of the clouds. Name him Ciq?neq?s."

When the child, Ciq?neq?s, grew old enough to go on errands, there was an old woman in the village who was his grandmother's sister. This old lady was very much inclined to be a sorceress. Ciq?neq?s knew about this. One day one of his uncles asked the boy to take his old woman over to his camp on the beach where he was clamming. She was quite old and was blind. Ciq?neq?s led the old lady to the camp, which was close to a precipice. Noticing this, the boy left the old woman at the camp and looked over the cliff. He saw there was a cave at the foot of the cliff that would be covered by water at high tide, but which was now dry, and that there were many large rocks scattered around the entrance.

He went back to the old woman and said: 'Let's go a little further.' He gave her her cane and led her down the edge of the cliffi nto the cave. He told her: 'While you're here, I'm going over to the house and I'll return.' Then he left quietly. Once outside the cave, he began to pile up stones until the entrance was completely blocked. Sometime later, the uncle noticed that it was high tide and thought to ask Ciq?neq?s how the old woman was. 'No animal will harm her,' said Ciq?neq?s. 'Is she away from the reach of the tide?' asked the uncle. 'Yes,' said the boy. Later, another old woman, missing her neighbor, told the uncle: 'You had better go and see what Ciq?neq?s has done with his grandmother's sister.' The uncle went, and not finding the old lady anywhere returned and said: 'She is not there.' Then the other old lady said to Ciq?neq?s: "What did you do with her?' The boy answered: 'I put her in a cave.' 'Why did you put her in there?' 'She fooled the world too much by means of her black magic.' Then the old woman exclaimed: 'You really are a child of the clouds, and only the clouds can punish you. But we must be patient with you, because if the clouds punish you by means of a deluge of water, the punishment will fall on us also.'

Another story in the Blackburn book concerns "Joaquin Ayala's Daughter," in which a daughter is born to parents who have consulted a sorceress to conceive; the daughter wanders away and is lost. She is found, but explains that she was following her mother up the mountain. "Then the old woman said to Joaquin Ayala and his wife, 'Here is your little girl. But she is not going to live, she is going to die. And I will tell you something else: this girl was not born naturally and she will not grow. She has the appearance of a girl, but she isn't. Take her now.'" The girl does die. The couple tries again, has another daughter, but she too dies. The "unnaturally born" child is strange, and cursed, and dies young--in fact, she's not even a child at all: "She has the appearance of a girl, but she isn't."

I don't know enough about Chumash culture to say whether or how these stories illuminate it. But the history of families and disability, across cultures, is full of folk explanations for a child's differences. There are admonishments against punishing the child (like in the Ciqneqs story), but also cold finger-wagging: Joaquin Ayala is told, your child is like this because you did something wrong. And we know that this belief is hardly confined to Chumash legends, or even to the past.

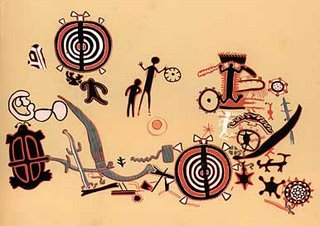

[Image above is taken from Grant Campbell, The Rock Paintings of the Chumash (UC Press 1965).]

No comments:

Post a Comment