Sunday, November 15, 2015

Christine la Barraque (c1878-1961), and more new disability content on Wikipedia

As I've mentioned, in recent years I've been putting some energy into Wikipedia. I like writing new entries there, because it feels like that's going to reach a much bigger audience than a journal article or a paywalled reference. And, as part of WikiProject Disability, some of my entries are about disability topics (of course). Since last BADD in May, I've started new entries for baseball coach Mary Dobkin, businessman Dwight D. Guilfoil Jr., South African activist Maria Rantho, wheelchair manufacturers Everest & Jennings, blind biochemist Dilworth Wayne Woolley, playground builders Shane's Inspiration, and blind singer/lawyer Christine la Barraque. I also built out an existing stub entry on educator Elizabeth E. Farrell, during the "Justin Dart Jr. Virtual Edit-a-thon 2015" in August.

None of these are exhaustive entries; they're a good solid start, I think, but if anyone reading this blogpost has more to add, with reliable sources to back up any new information, please jump in! Christine la Barraque has me especially curious right now (because I just wrote about her on Friday). She seems, pretty definitely, to have been the first blind woman to pass the bar in California; but was she the first in any state (as some sources suggest)? Was she the first blind woman to graduate from the University of California, in 1896 (when she was about 18 years old, by the way)? Anytime "the first" is on the table, there are questions and complications: who counts as blind? or graduating? or a woman? La Barraque was said to have been born in France, but exactly where is sketchy and mentions contradict each other. If she was, her parents came to America with a blind child, through immigration screens intended to prevent that scenario. So I would love to know more about them, too. (I think they lived in Tres Pinos or Paicines, California--when she was living in Boston at the time of the San Francisco earthquake, she sent a telegram to the governor of California asking after "my people in Tres Pinos.")

La Barraque wasn't an obscure singer or advocate; she performed for Helen Keller and Mark Twain, she was a founder and president of the San Francisco Workers for the Blind, she testified before the Massachusetts Legislature, she toured blind schools in Italy, she performed all over the US and apparently also in Canada. I've seen mentions of her working with disabled veterans after both World Wars, but not enough to include in the entry (yet).

Sunday, September 15, 2013

RIP: Anita Blair (1916-2010) and Betty G. Miller (1934-2012)

I first mentioned Anita Lee Blair (pictured at left, a white woman dressed in a dark suit, in a portrait with her guide dog Fawn) at this blog a few years ago, when David Paterson had become Governor of New York, and the topic of blind elected officials was in the news. Anita Blair was born in 1916, and became blind after head injuries sustained in a car accident, not long after graduating from high school (no seatbelts or safety glass in the 1930s). She graduated from the Texas College of Mines and Metallurgy; later she earned a master's degree as well. She was the first person in El Paso to receive a guide dog, a German shepherd named Fawn; she even made a short film about Fawn, to use on her lecture tour. Fawn and Anita made headlines in 1946, when they escaped a deadly hotel fire in Chicago. As far as anyone can tell, she was the first blind woman ever elected to any state legislature--she served one term in the Texas House of Representatives, 1953-55. (Here's a Time Magazine article mentioning that she won the Democratic nomination for that race.) She was also the only woman appointed to Harry Truman's Presidential Safety Committee, the first person to bring a service dog onto the floor of the US Senate, and later was a familiar presence in El Paso, vocal on talk radio and at city council meetings. Anita Lee Blair died in 2010, just a couple weeks before her 94th birthday, survived by her slightly younger sister Jean. Upon her passing, the Texas House of Representatives passed a resolution in tribute to their former member. There's a video of Blair talking about her life on youtube (not captioned), and her El Paso Times obituary included a photo gallery from news files.

Betty G. Miller's obituary turned up in this month's Penn State alumni magazine. (Miller is pictured at right, a white woman wearing a hat and glasses, with a big smile.) She was a deaf child of deaf parents, and learned ASL as a child at home, but was sent to oral education programs also, an experience that became a theme in her works. Betty Miller was an artist, an art educator (she had an EdD from Penn State, and taught at Gallaudet), an author, and by her own account the first deaf person to receive certification as an addiction counselor. In 1972 she had her first one-woman show, "The Silent World," at Gallaudet. Further shows followed over the next several decades, and a large-scale neon installation by Miller is in the lobby of the Student Activities Center at the Eastern North Carolina School for the Deaf. She was survived by her partner, artist Nancy Creighton. Some of Miller's works can be seen in this Wordgathering article by Creighton and at this Pinterest board.

Apparently, this is post #1000 at DSTU, according to Blogger (I suspect that count includes some drafts that didn't ever get posted, for various reasons). Happy 1000 to our readers, then!

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

January 17: John Stanley (1712-1786)

[visual description: a portrait of composer John Stanley, apparently in middle age, wearing a white powdered wig and a brass-buttoned coat; his eyes are noticeably scarred]

[visual description: a portrait of composer John Stanley, apparently in middle age, wearing a white powdered wig and a brass-buttoned coat; his eyes are noticeably scarred]Born on this date 300 years ago today, in London, English composer John Stanley (best click that link before or after Wikipedia goes dark on 18 January). Stanley was blind after a fall in early childhood. The boy turned out to be a musical prodigy while studying with the organist at St. Paul's Cathedral, and, at age 11, was appointed organist at All Hallows Church in Bread Street, a paid position. At fourteen he became organist at St. Andrews in Holborn, and at age 17 he completed a Bachelor of Music degree at Oxford.

Stanley married his copyist's sister, Sarah, a sea captain's daughter. He spent most of his career as organist to the Society of the Inner Temple. Handel was a frequent visitor to the church, to hear Stanley play. The admiration was returned: Stanley directed many Handel oratorios. Stanley's own baroque compositions were many and varied, from an opera to three volumes of organ music. (There are audio files of several Stanley compositions for organ at this site.) He was also elected governor of a Foundling Hospital, which mostly involved his advising the staff on hiring music teachers, and organizing fund-raising concerts.

Stanley's auditory memory and sensitivity were much remarked upon: it was reported that he never forgot a voice, and that he could judge the size of a room by sound. He also, apparently, had an adapted set of playing cards, with tactile markings at the corners, so that he could play whist with guests. Unfortunately for historians of such things, his family auctioned off all his possessions within weeks after he died, including his manuscripts and instruments.

Here's a YouTube video (which is really only a still image of an album cover) of John Stanley's Allegro (V) from Concerto op.2 no.1 in D Major:

I haven't discovered if there are any events marking his 300th birthday, but now we've marked it at DS,TU, anyway. And this early music editor blogger plans to produce some editions of Stanley's concertos this year.

BUT WAIT, THERE'S MORE!

In comments, Sue Schweik added the very exciting news that a UC-Berkeley musicology student, John Prescott, recently completed a dissertation about John Stanley.

Wednesday, September 07, 2011

J. A. Charlton Deas: Making Museums Accessible--A Century Ago

A young girl wearing a white pinafore and boots, using her hands to examine various ornithological specimens in a museum gallery; from the Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums uploads to Flickr Commons.

There have been several recent conferences on making museums accessible to blind patrons--and next month (October) is Art Beyond Sight Awareness Month--but the project of opening museum collections and art education to blind visitors, students, and scholars is much older than some might assume.

John Alfred Charlton Deas was curator at the Sunderland Museum in the 1910s. When he retired from that position, he looked into opening the museum's eclectic holdings to the students at the nearby blind school--and his efforts were met with enthusiastic encouragement. Soon, the museum was holding events that allowed the students to handle armor, zoological specimens, skeletons, paintings, sculptures, antique weapons, and vases, among other items. These sessions happened during times when the museum was otherwise closed to the public, like Sunday afternoons. Beyond the tactile experience, docents were present to give verbal information aloud, where the written labels were of little use. Lectures by local experts were arranged, for further information. Back at school, the students made clay figures based on what they touched and learned at the museum. The children's teacher wrote, "With minds better stored than their predecessors, they ought to be keener observers, better workers and more intelligent citizens." For some sessions, blind adults were also invited to participate. Deas published a paper on his efforts in 1913, but the idea didn't find many imitators at the time.

Natural History magazine ran an article on an American version of the concept in 1914. They reported that the American Museum of Natural History (in New York) started working with blind schools in 1909, by lending them models and giving guest lectures. In 1910 a fund was established to support field trips from blind schools and institutions to the museum, and to sponsor visiting exhibits from the museum to the schools.

A photographer recorded the 1913 tactile museum experiences run by Deas, and the Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums has made a set of 38 images available (with no-known-copyright status) on Flickr Commons.

Thursday, May 26, 2011

May 26: Moondog (1916-1999)

I wondered how, as a blind man, he managed to cross the street without an instant of hesitation until he showed me how he listened to traffic lights; I had never heard them before in this way.

--Philip Glass, on fellow composer Moondog; from his introduction to Robert Scotto, Moondog: The Viking of Sixth Avenue (Process 2007).

Born on this date in 1916, street poet and composer Moondog, aka Louis Thomas Hardin. He knew he was a drummer from an early age, starting with cardboard boxes as a little boy, and drumming in the high school band. Young Louis became blind after a farm explosion at age 16; he left his local high school and studied music and composition at the Iowa School for the Blind. He learned to read braille, and devoured books on music theory; he moved to New York City in 1943.

Within a few years of his arrival in New York City, he took the name "Moondog," and was performing his own compositions on the street, often in a Viking costume of his own devising. He was influenced by the jazz scene, and by city sounds. Moondog created his own instruments to make the sounds he wanted to hear: an Oo and a Trimba, among the most notable inventions. ""Performing in doorways was the only way to present my music to the public, but for playing on the streets I needed drums down close to the ground, so I used to design my own instruments and had a cabinet- maker put them together," he explained. Much of his music was recorded, including a 1957 children's album featuring vocals by Julie Andrews.

In 1974 he moved to Germany, and lived there the rest of his life, composing, recording and touring. A German woman, Ilona Sommer, transcribed his braille notation and otherwise assisted him. After Moondog's death in 1999, Sommer became the administrator of his estate. Samples of his compositions turn up in popular recordings today, most recently a snippet of his "Bird's Lament" in Mr. Scruff's "Get a Move On." And there are quite a number of Moondog recordings to be found on YouTube; here's one for example:

[Description: There are no moving visuals here, just a photograph of an album cover called "More Moondog," which features a closeup of his bearded face, eyes closed.]

Friday, June 18, 2010

HKMB: Seven Blind Women in History who were not HK

[Visual description: Photograph of a Rose Parade float in Pasadena, 2009, sponsored by the Lions Club, featuring a large framed image of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, with many many flowers below and "The Miracle Workers" as the caption; taken by me]

[Visual description: Photograph of a Rose Parade float in Pasadena, 2009, sponsored by the Lions Club, featuring a large framed image of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, with many many flowers below and "The Miracle Workers" as the caption; taken by me]As I said when we announced we'd be participating in the Helen Keller Mythbusting Blogswarm, we've already done some mythbusting posts about Helen Keller here at DSTU. But another invitation in the blogswarm call suggests bloggers write about other historical women with disabilities, so that the Helen Keller story has more context. Helen Keller was unique, like any individual is, but she was obviously not the only blind woman to do anything interesting, ever, anywhere.

So here are seven more historical names for starters, all but one of them born before Helen Keller. No living women included, just to keep it historical. And I know other people will write about Anne Sullivan and Laura Bridgman for this event, so I skipped them too. I wish the list was more diverse--mostly English speakers here, and a cluster of musicians--but it's a start and I hope others will add to it.

Let the parade begin!

1. Matilda Ann "Tilly" Aston (1873-1947) was a blind writer and teacher in Australia, founder of the Victorian Association of Braille Writers, and of the Association for the Advancement of the Blind. She is considered the first blind student enrolled at an Australian university. In addition to her writing and literacy work, she campaigned successfully for voting rights and public transit access for blind Australians. Aston edited a Braille magazine for many years, and was an enthusiastic correspondent in Esperanto.

2. Elizabeth M. M. Gilbert (1826-1885) was an Englishwoman who campaigned for blind education and employment. Her father was a college principal and bishop, and Elizabeth (blind from age 3) was educated in languages along with her seven sisters. With an inheritance to support herself, she founded the Association for Promoting the General Welfare of the Blind, and helped to found the Royal National College for the Blind. She also lobbied for the 1870 Education Act.

3. Fanny Crosby (1820-1915) was an American hymn writer, credited with writing over 8000 hymns (many under pseudonyms). She started as a student at the New York Institute for the Blind, and stayed on as a teacher of rhetoric and history. She had to resign at 38 when she married a fellow NYIB alumnus. Crosby played one of her own compositions at the funeral of President Grant in 1885. Said Crosby, "If perfect earthly sight were offered me tomorrow I would not accept it."

4. Frances Browne (1816-1879) was an Irish writer, blind from infancy. She began publishing poetry in her twenties, and succeeded well enough to move to London by 1852. She is best known for her children's book, Granny's Wonderful Chair and Its Tales of Fairy Times, but she also wrote three novels in the 1860s.

5. Charlotta Seuerling (1782?-1828) was a Swedish composer, writer, and musician. Charlotta's parents were both theatre professionals, so Charlotta had plenty of access to music as a child, and plenty of travel experiences too. When Per Aron Borg opened his Stockholm school for blind and deaf students in 1808, Charlotta was his first student, and her musical exhibitions were popular fundraisers. Charlotta Seuerling went on to help found the Institute for the Blind in St. Petersburg.

6. Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759-1824) was an Austrian composer and musician, a contemporary of Mozart's. She began performing as a teenager, singing and playing organ and piano. She commissioned works by Salieri, Mozart, and Haydn, and gave concerts in London, Paris, Frankfurt, Prague, and other major European cities. Maria Theresia von Paradis is credited with helping Valentine Haüy establish the first school for the blind in Paris in 1785. She also taught singing, piano and theory at her own music school for girls in Vienna.

7. Mary Mitchell (1893-1973) was a successful Australian writer who became blind in midlife. Faced with rapidly diminishing vision, she learned to type on a typewriter and use a dictaphone, and wrote eight more novels with them. Mitchell was vice-president of the Braille Library of Victoria. She also wrote Uncharted Country (1963), about the practical aspects of living with blindness.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

June 3: The Andrew Heiskell Library (b. 1895)

In 1909, Ferry's assistant on the project, and one of the library's trustees, educator Clara A. Williams, wrote a plea in the New York Times, defending New York Point System against other braille formats. Her letter points to the state of flux such efforts faced just a century ago: "It seems a dreadful thing to me, for those living in New York State, and New York City, to allow any persons to come in from other States with a system of print which can be proved to be inferior, and tell us what we should do in our public schools, &c.... Miss Keller is certainly a wonderful woman, but she would, it seems to me, be biased in favor of any type for which her friends stood and it would be most natural for her to take the stand chosen by her teacher..." There were also concerns about whether the library would include a Bible (when "nearly every reader at the library has been presented with a Bible and has it in his own home").

The collection became part of the NYPL in 1903, and expanded over the years, in size, in format, and services offered. The technological history of recordings in the twentieth century is reflected in how audio books were prepared for blind readers over the years: hard discs, flexible discs, cassettes, and digital files have all taken their turn, in tandem with the devices required to play them.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

13 February: The Beating of Isaac Woodard (1946)

[Image description: black-and-white photo of Isaac Woodard, seated, wearing a uniform and large round sunglasses. A woman is standing next to the chair, with her arm behind Woodard.]

[Image description: black-and-white photo of Isaac Woodard, seated, wearing a uniform and large round sunglasses. A woman is standing next to the chair, with her arm behind Woodard.]What does it cost to be a Negro? In Aiken, South Carolina it cost a man his eyes.

--Orson Welles, in a September 1946 radio broadast

On this date in 1946, Isaac Woodard (1919-1992) was on a long bus ride from Georgia, returning to his family in North Carolina. Woodard was African-American, and grew up in the South, but he was also in uniform, freshly discharged from the US Army with medals earned for his wartime service. Surely, he could use the next rest stop without any fuss?

The driver allowed him to do that; but the driver also contacted police, who took Woodard off the bus at the next stop in Batesburg, South Carolina. After being removed from the bus, Sgt. Woodard was beaten with nightsticks and taken to the town jail. The next morning, Woodard woke up blind. Both of his eyes had been irreparably damaged in a beating that he didn't remember clearly. He was released from jail, brain-injured and blind, and received no medical care for at least two days after the event. His family reported him missing after three weeks; only then was he identified and moved to an Army hospital for care.

Woodard's story was publicized by the NAACP; Orson Welles called for the punishment of the policemen involved; a federal case was brought, but the chief of police was cleared of all charges. Although he was not blinded during his war service, the Blinded Veterans Association made an exception in his case, and welcomed him as a member. Woodard moved to New York after he recovered, and died in a military hospital there in 1992.

The abuse faced by Woodard and other returning soldiers was part of President Truman's reason for issuing Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces. Woody Guthrie wrote the song "The Blinding of Isaac Woodard" to retell the story in ballad form at a concert in support of Woodard held in New York City in 1946 (also featuring Cab Calloway, Billie Holliday, Milton Berle, and Orson Welles).

Want to teach about the Woodard case? Documents related to his story are collected online here, courtesy of Andrew H. Myers, for classroom use.

Further reading:

Robert F. Jefferson, "'Enabled Courage': Race, Disability, and Black World War II Veterans in Postwar America," The Historian 65(5)(2003): 1102-1124.

Kari Frederickson, "'The Slowest State' and 'Most Backward Community': Racial Violence in South Carolina and Federal Civil-Rights Legislation, 1946-1948," South Carolina Historical Magazine 98(2)(1997): 177-202.

Tuesday, February 09, 2010

"Blind Singer," William H. Johnson

Blind Singer

Originally uploaded by Smithsonian Institution

[Visual description: An art print depicting two stylized figures, male and female, with dark skin; the man's eyes are closed, the woman's are open; the man holds a tambourine and the woman a guitar; both are dressed in the style of the 1930s, but the colors of their clothing are unusually bright]

The Smithsonian's latest batch of uploads to the Flickr Commons project is a collection of prints by William H. Johnson (1901-1970), an African-American artist who experienced mental illness and was institutionalized for the last twenty-three years of his life. The image above, "Blind Singer," is typical of his work c.1940--two-dimensional figures, bright colors, and depictions of everyday scenes. The National Museum of American Art holds over a thousand works by Johnson.

Friday, August 28, 2009

Another "hilarious" blind cartoon character ?!?!?

[Visual description: animation still; the human character is an African-American woman wearing a white headscarf, shawl, and dress, sunglasses, bracelet, ring, and large gold earrings; she's holding the head of a large snake in her hands, and smiling at it.]

[Visual description: animation still; the human character is an African-American woman wearing a white headscarf, shawl, and dress, sunglasses, bracelet, ring, and large gold earrings; she's holding the head of a large snake in her hands, and smiling at it.]Hoo-boy. Get ready for Mama Odie, the fairy godmother in Disney's new feature, "The Princess and the Frog." She's a 200-year-old swamp-dwelling seer and she's blind (get it? get it?). She has a "seeing-eye" snake. Yeah, that won't confuse any children about the work of service animals...

Thursday, April 30, 2009

New Image Database from the NLM

[Image description: Stylized portrait of a man, standing at a podium, wearing a powdered wig, ruffled white shirt, and dark glasses.]

[Image description: Stylized portrait of a man, standing at a podium, wearing a powdered wig, ruffled white shirt, and dark glasses.]The National Library of Medicine has significantly changed their website titled Images from the History of Medicine-- and the over 60,000 images (portraits, photographs, drawings, caricatures, posters, etc.) include a lot of images of interest to historians of disability. In a quick riffle, I found 1838 drawings of "idiots" in Paris, 1791 diagrams for slings and prosthetic devices, and of ear trumpets, and the lovely 1796 portrait at left, of Dr. Henry Moyes (c1750-1807), a noted Scottish chemistry lecturer who was blind after surviving smallpox as a small child. There are many more recent (1970s and later) photographs and posters and pamphlet covers and such as well.

Thursday, February 26, 2009

February 26: John Puleston Jones (1862-1925)

John Puleston Jones was born on this date in 1862, at Llanbedr. He was 18 months old when he became blind from an accidental injury. His mother (who wrote poetry as "Mair Clwyd") is credited with insisting that he learn independence skills in childhood. Puleston Jones was an excellent student through school, and after a year at the College for the Blind in Worcester he went on to Glasgow University and Balliol College, Oxford. He graduated with first-class honors in modern history.

Puleston Jones was always interested in Welsh culture and history, and helped to found the Dafydd ab Gwilym Society at Oxford in 1886. In 1888 he was ordained as a pastor. He served in various churches, published his sermons and theological essays, and wrote articles for a Welsh pacifist periodical (Y Deyrnas) during World War I. He is best remembered today for devising adaptations of Braille to fit the Welsh language--adaptations that apparently remain in use today.

Today, a plaque marks the house where the Rev. Dr. Puleston Jones was raised, in Bala.

Thursday, January 15, 2009

Patrick Byrne ( c.1794 - 1863)

Patrick Byrne, about 1794 - 1863. Irish Harpist

Originally uploaded by National Galleries of Scotland

[Image above (click through for a better version): vintage photo of an older man, wearing blanket-like draped robes and a laurel wreath on his head, seated at a harp]

The National Galleries of Scotland began uploading images to the Flickr Commons project this week--and in the first batch of 107 photos, this image of blind Irish harpist Patrick Byrne (17??-1863). There was a long tradition of blind harpists in Ireland before Byrne--including Arthur O'Neill (1737-1816), Echlin O'Cahan (b. 1720), Thady Elliott (b. 1725), Owen Keenan (b. 1725, aka "The Blind Romeo of Killymoon"), Denis O'Hempsy (1695-1807--yes, I typed that right, he was believed to be 112 at his death), and Rory "Dall" O'Cahan (b. 1646, the Dall in his name indicates his blindness). And of course, Carolan (1670-1738) (thanks to Kathie S. for the reminder there!).

Last year marked the 200th anniversary of the 1808 founding of the Irish Harp Society in Belfast, one of the first schools in the world for blind musicians. In its first years, the school taught music in Irish, because the technical terms the teachers used were Irish words. So the school was considered both a vocational training program and a cultural preservation effort.

Sunday, January 04, 2009

And speaking of Braille...

Friday, December 05, 2008

Helen Keller's Flickring

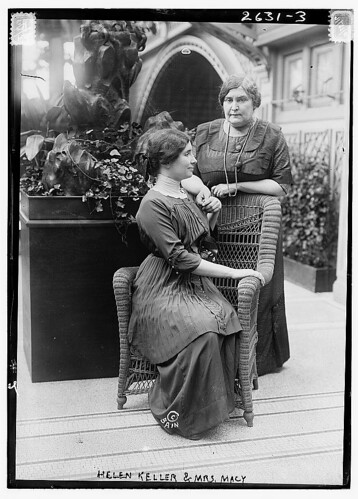

Helen Keller and Mrs. Macy (LOC)

Helen Keller and Mrs. Macy (LOC)Originally uploaded by The Library of Congress

This week's batch of Flickr Commons uploads from the Library of Congress's G. G. Bain Collection includes a series of photos of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy, taken in some kind of conservatory or museum. In the photo I've featured here, Keller is seated in a wicker chair, and posed in profile, while Macy stands behind the chair and is seen face-on. Both women wear long dark dresses and have long hair arranged in low chignons at the nape. The Bain Collection photos are from 1910-1915.

If you have more information about the occasion or location of these photos, you can add that to the photos at Flickr. (The photos can also be tagged by visitors.)

Monday, November 17, 2008

November 17: Winifred Holt (1870-1945)

[Image description: black-and-white archival photo of two men seated at a table, in French military uniforms; they have their hands on a small checkerboard; one man appears to have his eyelids closed, and the other has fabric patches over both eyes; behind them, a woman in seated, and has her own hand stretched toward the checkerboard]

[Image description: black-and-white archival photo of two men seated at a table, in French military uniforms; they have their hands on a small checkerboard; one man appears to have his eyelids closed, and the other has fabric patches over both eyes; behind them, a woman in seated, and has her own hand stretched toward the checkerboard]Co-founder of Lighthouse International (formerly the New York Association for the Blind) Winifred Holt was born on this date in 1870, in New York City, the daughter of publisher Henry Holt. She was a force in early twentieth-century advocacy --she and her organization worked for inclusion of blind children in New York public schools, for summer camps, vocational training programs and social groups run by and for blind people, for rehabilitation of blinded WWI veterans. She also worked for changes in medical protocols to prevent a common cause of blindness in newborns. She encouraged similar "Lighthouses" to operate in other cities around the world. Many of the projects she started continue in some form today.

In the photo above (found here, in the Library of Congress's Bain Collection), Holt is seen teaching newly blind French soldiers to play checkers in a rehabilitation program in France (Holt received the Legion d'Honneur for her wartime work there). Holt trained as a sculptor when she was a young woman; her best known work is a 1907 bas-relief bronze portrait of Helen Keller, online here. She also wrote a biography of blind English MP and postmaster Henry Fawcett.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Enrique Oliu

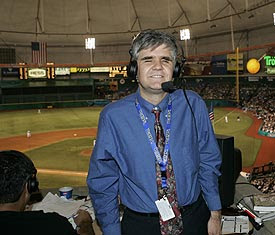

[Image description: Enrique Oliu standing in a press box, with a baseball diamond in the background; he's wearing a shirt, tie, headphones, and credentials, and smiling; he has dark eyebrows and greying hair]

[Image description: Enrique Oliu standing in a press box, with a baseball diamond in the background; he's wearing a shirt, tie, headphones, and credentials, and smiling; he has dark eyebrows and greying hair]I always run into skeptical people, but I've never had any problem doing my job.

--Enrique Oliu

Enrique Oliu is the Florida broadcaster covering the World Series for Spanish-language audiences in Tampa Bay. Oliu is blind. Born in Nicaragua in 1962, he attended the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind in St. Augustine as a child, and graduated from the University of South Florida. He's been covering baseball professionally since 1989, and now covers all of Tampa Bay's games, as well as spring training camps in Mexico and Venezuela. "I played this sport and a bunch of others. Adapted, but I played. Blind or not blind, I have an opinion and I just state mine. That's what people want."

Monday, August 04, 2008

Back from the Disability History Conference

One example, for starters: Christian Gray (1772-c1830) was a farmers' daughter from near Perth, who became blind when she survived smallpox as a little child. She was read to, daily, for her education; in time, she began composing poetry, and her first volume of poems was published in 1808. She pointed to Milton and Ossian as her predecessors, and wrote poems about being blind (I can't find any of those verses online yet, though).

Monday, June 23, 2008

"Reflections On the Physical and Moral Condition of the Blind (1825)"

The Holman Society Presents

Selected Reflections On the Physical and Moral Condition of the Blind (1825):

A Conversation and Performance

Written By Therese-Adele Husson

Introduced by Catherine J. Kudlick

Performed by Carrie Paff$5-20 sliding scale at the door

No one turned away for lack of funds.

The Holman Society invites you to a live performance of selected passages

from Reflections: Writings of a Young Blind Woman in Post-Revolutionary France (NYU Press 2001). This brief yet surprisingly expansive treatise on blindness was probably dictated in desperation to one or more sighted scribes in the early nineteenth-Century French equivalent of a renter's résumé, only to be rejected, set aside, and lost for almost two-hundred years. The blind author's first-hand observations about blind people and their social status, rules for marriage, prospects for romance, and appropriate pedagogical approaches paint a portrait of a bygone place and time with hauntingly familiar themes which remain with us to this day. The style is 100% over-the-top, unedited nineteenth century, translated French hyperbole, with all of the linguistic curlicues and semantic serifs one could possibly wish for. Blind women are referred to as "female companions of misfortune," and chapters have titles such as "On the Inflection of a Sweet Voice on the Heart and Senses of a Blind Person." Nevertheless, an amazing amount of what she has to say strikes strong resonant chords in today's blind world. Even when her observations seem antique or deliberately demure, her writing raises deep questions as to why her experience was what it was, and why ours is what it is (or isn't).

We welcome Carrie Paff - a treasure of stage and screen - who will read for us, and Professor Catherine J. Kudlick - the manuscript's re-discoverer and translator - who will help us to place Adele Husson in her proper historical context.

The relaxed wine and cheese reception following the presentation will be an

extraordinary opportunity for open discussion and exchange of ideas. We

anticipate attendees from a rich maelstrom of interlocking backgrounds

including disability and gender studies, history, disability rights,

rehabilitation and rehabilitation engineering, and of course the Holman

Society and broader Bay Area blind community.

This event promises to be thoroughly entertaining and thought-provoking,

and follows in the informal, yet deeply stimulating tradition of the Holman

Society. We hope you will attend.