A few years ago, I started a Flickr group for disability history images--called, cleverly enough, Disability History. Today it contains over 200 images contributed from libraries and personal collections, including images of family life, activism, art, technology, war--all topics I was hoping it might address. It's true that most of them are black-and-white, or rather that warm sepia tone that makes the past look maybe a little rosier than it should. But some are in color, because history didn't stop with the invention of color film, and indeed, history is still happening. I certainly welcome contributions to the growing collection of recent disability history images there--we could especially use more images from non-US/UK contexts. Here's a sampling of the generous additions so far, by the Flickr users credited in each caption:

|

| Lilibeth Navarro leads a Not Dead Yet protest in Hollywood, on a sunny March day in 2005, against the film "Million Dollar Baby" (which went on to win best picture). In the image, several protestors in power chairs roll past stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, with walking protestors behind them. (I'm just barely visible at the way back.) Photo by Cathy Cole. |

|

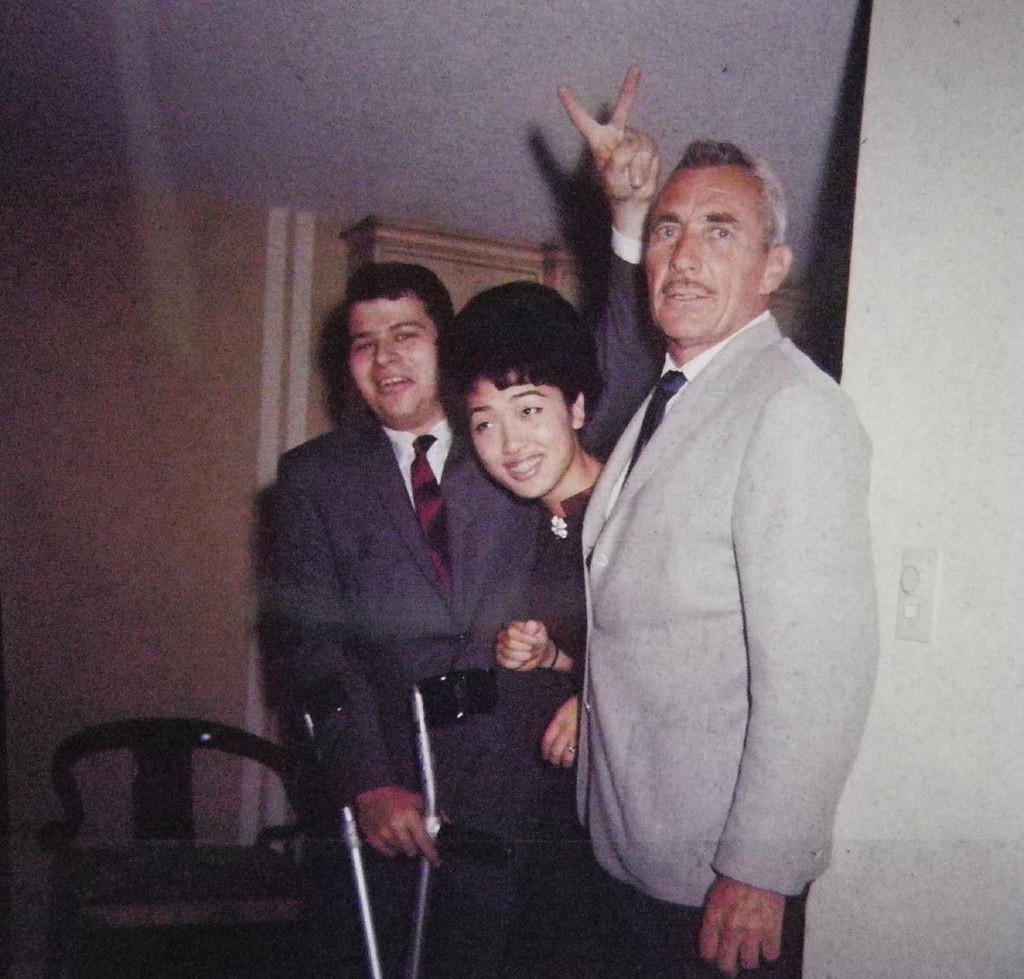

| Candid undated snapshot from shows three people. The young man at rear, left, is violinist Itzhak Perlman, smiling and flashing a peace sign; his arm crutches are both visible. The other two people are not identified; one is an young Asian woman, and one is an older white man with a mustache. Photo from the account of Erin Corda, who writes, "I found this 120 color transparency of Issaac Perlman while clean out my fathers sheet music cabinet." |

|

| Informal snapshot from the 1960s, shows a smiling blonde little girl with glasses, a green print dress with very white collar and cuffs; white socks and black maryjanes. She's standing outdoors, in front of blooming flowers and a stone wall. Photo from the account of Joshua Black Wilkins, who writes, "My aunt Karen. Who had Downs Syndrome." |

| |||||

| Art piece by Al Shep, titled clinical waste / institutionalisation, which addresses the history of asylums. In the image, two trash bins are marked with stenciled block lettering and images. The trash bin on the left says "Empty Unreal Unable to Feel" with the face of a woman labeled "Annie, May 1900 Melancholia Recovered"; the larger blue bin on the right is stenciled with a definition of "institution" (the wording wraps around the bin so we can only read part of the definition, with words like structure, social, behaviour, community, permanence, rules). Other images of the project are here. Photo by Al Shep. |

|

| A portrait of Jack Smith, of Rhodell, West Virginia, made by photographer Jack Corn in 1974; he is a white man in his early 40s with sandy hair. His arms are crossed, showing his watch and wedding ring; he does not have legs. Jack Smith was disabled in mining accident, and became active with the United Mine Workers Union during his eighteen-year struggle for worker's compensation. Photo from the US National Archives, Documerica set, in Flickr Commons. |